|

|

ALONG CAME A SPIDER ... |

OCTOBER 'tis the month of goblins, ghosts, trick or treaters ... and... SPIDERS!

|

|

ALONG CAME A SPIDER ... |

OCTOBER 'tis the month of goblins, ghosts, trick or treaters ... and... SPIDERS!

Spiders use our ponds during all the seasons, but it seems our senses are more

alert to `scary ` things at this time! I don't know about your pond, but at ours, spiders

are among the more numerous and visible residents. Some build webs between the

reeds, others lie in ambush among the petals, and there are even spiders who go

fishing! In this article we'll try to put aside any misgivings we may have and learn about

these ancient and interesting critters.

So just what is a spider? Well, for one thing it is NOT an insect. Insects have 6

legs and 3 body parts. Spiders are arachnids, having 8 legs and 2 body parts.

There are more than 30,000 known kinds of spiders, but scientists believe there may be

as many as 50,000 to 100,000 kinds. Some kinds are smaller than the head of a pin.

Others are as large as a persons hand. This article will concentrate on those found

around ponds in Northern America.

Web-spinning spiders

often live in the grass, shrubs, or trees around our ponds. They cannot catch

food by hunting because of their poor vision. Instead, they spin webs to trap insects.

Ever wonder how a web-spinning spider keeps from becoming caught in its own web?

Well, it's because when they go walking across their web, they grasp the silk lines with

a special hooked claw on each foot.

Web-spinning spiders

often live in the grass, shrubs, or trees around our ponds. They cannot catch

food by hunting because of their poor vision. Instead, they spin webs to trap insects.

Ever wonder how a web-spinning spider keeps from becoming caught in its own web?

Well, it's because when they go walking across their web, they grasp the silk lines with

a special hooked claw on each foot.

There are even several types of web-spinning spiders. Tangled-web Weavers

spin the simplest type of web. Their web consists of a jumble of threads attached to

a support. At our pond, cellar spiders spin tangled webs in dark places. One cellar

spider that looks like a daddy longlegs has thin legs more than 2 inches (5 centimeters)

long. The comb-footed spiders spin a tangled web with a tightly woven sheet of silk in

the middle.  The

sheet serves as an insect trap and

as the spider's hideout. These spiders get their name from the comb of hairs on their fourth pair of legs. They use

the comb to throw liquid silk over an insect to trap it. The black widow is a comb-footed spider. At this time of

the year the black widows find the sun drenched rocks ringing parts of our pond irresistible. They are the only

North American spider whose bite is poisonous that are likely to be building webs around our ponds.

The

sheet serves as an insect trap and

as the spider's hideout. These spiders get their name from the comb of hairs on their fourth pair of legs. They use

the comb to throw liquid silk over an insect to trap it. The black widow is a comb-footed spider. At this time of

the year the black widows find the sun drenched rocks ringing parts of our pond irresistible. They are the only

North American spider whose bite is poisonous that are likely to be building webs around our ponds.

Funnel-web Weavers might also live around our ponds. They make large webs that  they spin in the grass or under

logs. The bottom of the web is shaped like a funnel. This funnel

serves as the spider's hiding place. The top of the spider's web forms a large sheet of silk that spreads out over

grass or soil. When an insect lands on the sheet, the spider runs out of the funnel and pounces on the victim.

they spin in the grass or under

logs. The bottom of the web is shaped like a funnel. This funnel

serves as the spider's hiding place. The top of the spider's web forms a large sheet of silk that spreads out over

grass or soil. When an insect lands on the sheet, the spider runs out of the funnel and pounces on the victim.

Sheet-web Weavers spin thin sheets of silk between blades of grass or branches of shrubs or trees. These

spiders also spin a net of crisscrossed threads above the

sheet web. When a flying insect hits the net, it bounces into the sheet web. Often, an insect will fly directly into

the sheet web. A spider, which hangs beneath the web, quickly runs to the insect and pulls it through the webbing.

Sheet webs last a long time because the spider repairs any damaged parts.

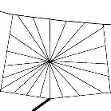

But it is the Orb

Weavers that build the most beautiful and complicated webs.

They weave their round webs in open areas, often between reed or flower stems. Threads of dry silk extend from

an orb web's center like the spokes of a bicycle wheel. Coiling lines of sticky silk connect the spokes, and serve as

an insect trap.

But it is the Orb

Weavers that build the most beautiful and complicated webs.

They weave their round webs in open areas, often between reed or flower stems. Threads of dry silk extend from

an orb web's center like the spokes of a bicycle wheel. Coiling lines of sticky silk connect the spokes, and serve as

an insect trap.

Some orb weavers lie and wait for their prey in the center of the web. Others attach a

trap line to the center of the web and then hide in the nest near the web, and hold on to the trap line. When an

insect lands in the web, the line vibrates. The spider darts out and captures the insect. Many of the orb weavers at

our pond spin a new web every night. It takes about an hour, and is interesting to watch. Sometimes they eat their

old

webs to conserve silk and to make use of the nutrients of any tiny insects caught in the web. Other orb weavers

repair or replace damaged parts of their webs.

Ever wonder just how the Orb Weaver makes that web? Well, apparently the very first strand is the hardest.

What is done is the spider releases a sticky thread that is blown away with the wind. If  the breeze carries the silken line to a spot where it sticks, then the first bridge is formed. The spider

cautiously crosses along this thin line, reinforcing it with a second line. She reinforces the line until it is strong

enough.

the breeze carries the silken line to a spot where it sticks, then the first bridge is formed. The spider

cautiously crosses along this thin line, reinforcing it with a second line. She reinforces the line until it is strong

enough.

After this the spider

constructs a loose thread and then she constructs a Y

shaped thread.

After this the spider

constructs a loose thread and then she constructs a Y

shaped thread.

These are the first three

radii

of the web. Next a frame is constructed to attach the other radii to.

These are the first three

radii

of the web. Next a frame is constructed to attach the other radii to.

Then the radii are completed.

The distance between

Then the radii are completed.

The distance between  them is so wide that the spider can span the width.

Now a

them is so wide that the spider can span the width.

Now a  sticky thread is

spiraled in and the web is now completed.

sticky thread is

spiraled in and the web is now completed.

After a night's use, the web may become worn out. The spider then removes the silk in the morning leaving

only the first bridge line. After a rest during the daytime, the spider constructs a new web in the evening. If the

spider's catch was low and

the web is not heavily damaged, the web may stay during the day and be reused after minor repairing.

By the way: No two spider webs are the same!

Spiders are helpful to people because they eat harmful insects.

Spiders not

only eat grasshoppers and locusts, which not only destroy our beautiful pond plants but also destroy crops, but they,

of course, also eat flies and mosquitoes, which besides giving painful bites and being a nuisance, can also carry

diseases. Although spiders feed mostly on insects, some spiders capture and eat tadpoles, small frogs, small fish,

and mice. Spiders even eat each other. Most female spiders are larger and stronger than male spiders, and

occasionally eat the males. The black widow derived her name from this trait. The spiders who do eat those larger

mentioned things are not web-makers however but hunting spiders.

Spiders not

only eat grasshoppers and locusts, which not only destroy our beautiful pond plants but also destroy crops, but they,

of course, also eat flies and mosquitoes, which besides giving painful bites and being a nuisance, can also carry

diseases. Although spiders feed mostly on insects, some spiders capture and eat tadpoles, small frogs, small fish,

and mice. Spiders even eat each other. Most female spiders are larger and stronger than male spiders, and

occasionally eat the males. The black widow derived her name from this trait. The spiders who do eat those larger

mentioned things are not web-makers however but hunting spiders.

Next month we'll peek into the lives of the hunting spiders, one kind of which actually goes fishing under

water!

A special thank-you to Ed Nieuwenhuy of the Netherlands for use of photos and information from his Spider Pages.

Links to his wonderful and informative sites will be provided next month.

Help was also provided by Ron Lyons.